NEW YORK (MarketWatch) -- One unique type of indexed investment is rapidly gaining popularity: "Structured products" are short-term to intermediate-term notes, which normally would pay interest. These don't. Instead, their payoff usually depends on the performance of an index, or maybe a commodity price such as oil or gold.

The required performance is specified in the offering documents for these products. For instance, one product may pay off if the Dow Jones Industrial Average exceeds a particular level by the maturity date, while another pays if the Dow falls below a certain level. It's all in how an investment bank structures the product -- which is another way of saying what the bankers think will sell.

Actually, the Dow examples are of the plain-vanilla variety. Many structured products nowadays are increasingly sophisticated, not to say complex, and are incorporating strategies as well as securities.

Consider, for example, a $2.2 million issue of "Buffered Return Enhanced Notes" that J.P. Morgan Chase & Co.issued last month.

This product essentially is a bet that the commercial and residential real estate markets will recover by April 10, 2010, when the notes mature. The index-linked assets in this product consist of a basket of three ETFs: iShares Dow Jones U.S. Real Estate Index Fund, Financial Select Sector SPDR Fund,

This basket -- in which the iShares real-estate fund accounts for 60% and the other two ETFs are 20% each -- was priced on April 2. J.P. Morgan Chase set this level (a total of $51.24 for the basket) at 100. If the basket price level is higher in two years, investors get their principal back plus two times the percentage gain of the basket.

This is the "enhanced" part of the structure. If the basket ends up at 112, the note would pay out $1,240 for each $1,000 invested, or a 24% total return. The upside potential return is capped at 42%, which means anything more than a 21% increase in the basket does nothing for the investor.

But what if the bottom falls out and the basket ends 30% lower at 70? The investor receives $850 for each $1,000 invested. That's only half of the basket's drop because the note offers protection against a decline of 15% -- the "buffered" part of the structure. If the basket fell to zero, the investor would still get $150 for each $1,000 face amount.

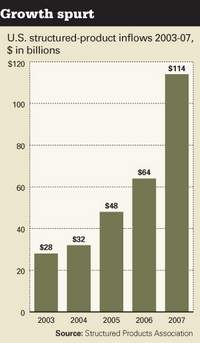

Structured products appeal to investors for a variety of reasons, not least of which is the usually relatively short wait to find out if they've won or lost. According to the Structured Products Association, $114 billion of these instruments were issued last year, up from $64 billion in 2006. So far, this year is on track to reach $120 billion, a 5% increase.

That's impressive growth during a time of turbulence in many markets and asset classes. Keith A. Styrcula, chairman and founder of the association, says one of the driving factors is a "profound shift in investor thinking -- that active management isn't worth the extra cost."

Individual investors take about 45% of structured products and 55% go to institutions, Mr. Styrcula says. "Only 5% to 10% of the investment advisers and brokers are familiar with structured products now. As more of them become so, we'll see growth in the number of individuals participating either directly or through certain mutual funds," he adds.

Rules and caveats

If you're considering a structured product, what should you be aware of?

1. Structured products are sold, not bought. The broker, adviser or somebody similar is going to pitch these investments, and until that happens you probably wouldn't even know they exist. These people want a piece of your investment capital, and most likely haven't given your goals or risk appetite much thought. It's up to you to decide whether the product being offered fits your portfolio and investment strategy. If you can't decide, just say "no."

Indeed, Norway's regulators recently banned structured products from being offered to most individual investors because their "risks are not well understood." This move came after some Norwegian municipalities were burned in the subprime mortgage debacle.

2. Only about 10% of structured products are listed on exchanges. The rest exist in a dimly lit over-the-counter realm. That means you will not necessarily be able to follow the interim pricing of these products, although you could track the publicly traded components such as ETFs.

And there isn't a liquid aftermarket in case you want to -- or need to -- bail before the products mature. Some investment banks say they will buy back the products they created from investors, but you may have noticed that some of these banks run out of money occasionally. In our example above, J.P. Morgan Chase declares it "intends to offer to purchase the notes in the secondary market but is not required to do so."

One notable exception is the growing number of exchange-traded notes. These ETNs were introduced to establish access to markets that are not readily available to many investors, such as commodities and currencies. They are notes structured with distant maturities that allow for exchange trading, and some of them have built up a decent daily volume.

3. Structured notes introduce credit risk into investments that otherwise wouldn't have any. The vast majority of these products are notes that are backed by the issuing banks. If the bank goes belly-up, structured-note investors are left holding the bag. Ideally, you'd perform due diligence on the bank's credit rating before you put money into one of its structured notes.

4. Many structured products offer "principal protection." That is, the investor is guaranteed to get capital back with possibly some extra kicker if the linked index performs favorably. The J.P Morgan Chase example above isn't one of these, but many investors insist on this protection. It changes the risk factor from one of potential loss to one of tying up your money for a period without any recompense.

This kind of structured product plays into what many behavioral finance professors have been telling us: Some people hate to lose money more than they hate to not make money.

Structured products are ingenious, fascinating vehicles. They require careful thought on your end about whether you should take them for a spin, or kick the tires and walk away.

John Prestbo is editor and executive director of Dow Jones Indexes.

Thursday, May 22, 2008

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)