Here's what you need to know about exchange-traded notes. Starting with: What are they?

By SHEFALI ANAND

August 4, 2008; Page R2

Wall Street firms may be facing all sorts of financial woes, but that hasn't stopped them from churning out a new type of product: exchange-traded notes. The big question: Should you buy?

Exchange-traded notes, or ETNs, are basically debt instruments in which the issuer promises to pay a specified return, usually based on a market index's performance, minus specified fees. Similar to their exchange-traded-fund cousins, ETNs trade throughout the day like stocks.

The issuer typically is a large financial-services firm such as an investment bank or commercial bank. Staking out market share have been Deutsche Bank AG, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., Morgan Stanley and UBS AG, among others.

So far this year, 63 ETNs have been launched, compared with 22 in all of 2007. In contrast, ETF issuance has slowed, with about 104 launches so far this year, below the pace that resulted in 259 new ETFs last year. Research firm Morningstar Inc. now tracks 89 ETNs with $7.3 billion in assets, versus 732 ETFs with about $586 billion under management.

A majority of ETNs provide exposure to commodities, while others focus on currencies and the

stock markets of single countries. For whom are these investment vehicles best suited? And are they dicey if they are issued by Wall Street firms? Here is what you need to know:

Q: What is the history of these products?

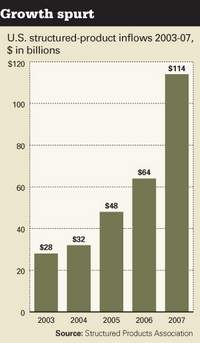

A: These aren't new inventions. Since the 1990s, banks have created "structured notes" for wealthy clients and institutional accounts, often with bells and whistles. For instance, a note might promise an investor 1.2 times the return of the Standard & Poor's 500-stock index over two years, up to a capped amount, and it might promise to give investors at least some of their principal back in the event of a decline.

When stock markets are distressed, think exchange-traded funds -- specifically bond funds.

In 2006, Barclays Bank PLC, a unit of Barclays PLC, issued a fairly simple structured note that could be traded on a stock exchange in small units. Its first two ETNs focused on well-known commodity-basket indexes: iPath S&P GSCI Total Return Index ETN, which tracks the Standard & Poor's Goldman Sachs Commodity Index, and iPath Dow Jones-AIG Commodity Index Total Return ETN, which tracks an index from American International Group Inc. and Dow Jones & Co., a unit of News Corp. and the publisher of this newspaper.

Q: Who uses them and why?

A: ETNs have become popular among financial advisers looking for ways to put their clients into certain asset classes that previously were difficult to tap.

For instance, only a handful of mutual funds and ETFs provide exposure to commodities. This is partly because mutual funds and ETFs are governed by mutual-fund regulations that prohibit direct ownership of commodities and restrict the level of financial futures and debt leverage that can be used to juice returns. (The well-known SPDR Gold Shares is often referred to as an ETF, but it actually is a complicated "grantor trust" in which gold bullion is held in trust for the benefit of shareholders.)

Since ETNs aren't governed by the same laws, they have more liberty to invest in complex financial derivatives and use heavy leverage. "A lot of these [ETNs], you just couldn't pull them off in an ETF structure," says Brian Kazanchy of financial-advisory firm RegentAtlantic Capital LLC, in Chatham, N.J.

Of the 54 commodity ETNs on the market, some track a diversified commodity index and others

focus on a single commodity, like coffee or sugar. The largest is iPath Dow Jones-AIG Commodity Index Total Return, at nearly $3.4 billion.

Some ETNs issued by Deutsche Bank promise to double the return of a commodity, like gold, and others promise to double the inverse of the returns, making it an ultrabearish bet.

Two-thirds of ETNs currently hold less than $10 million apiece, according to Morningstar.

Q: Should small investors buy ETNs?

A: Financial advisers say investors should fully understand these products before jumping in. They say individuals probably should steer clear of the niche ones, such as single-currency or single-commodity ETNs, or those that promise to double the returns of an index or double the inverse of a commodity's performance.

Lou Stanasolovich, a financial adviser in Pittsburgh, believes that all investors should have commodity exposure of 5% to 10% in their portfolio. He recommends that individuals stick to a broad-based ETN like the iPath Dow Jones-AIG Commodity Index Total Return.

He says investors should start with a 1% to 3% allocation, and add another percentage point or two as they get more comfortable with these instruments.

Investors also should diversify among ETN issuers to reduce exposure to the debt of any single firm. "You'd want less than 5% in any one counterparty," says RegentAtlantic's Mr. Kazanchy. Investors might want to build up to a 10% allocation to commodities by using commodity ETNs in conjunction with commodity ETFs and mutual funds.

"It is important not to put all your eggs in one basket," says Nelson Lam, an investment adviser in Lake Oswego, Ore.

For the complete article from the Wall Street Journal, click here.

Monday, August 4, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment